Nostalgia for the 1990s remains heavy. Just look at all those stadiums and parks the Gallaghers are filling. Football from the late 20th century has a similar cachet. No VAR, no sportswashing; just good, hard, honest, simple fare, when men were men and pressing was what you did to your Burton suit. If the past is a foreign country then a recent BBC Archive release is a primary source of a time when the continental import remained exotic and not the dominant division of labour.

“Is English Football In Crisis?” asks an edition of On The Line in October 1993, broadcast the night before Graham Taylor’s England played a key World Cup qualifier in Rotterdam. You know the match: Brian Moore correctly reading Ronald Koeman’s free-kick – “he’s gonna flick one” – and the pathos of Taylor’s hectoring of the linesman as England’s hopes of qualifying for USA ’94 sink into the briny.

Such is the soap opera of the English game – its warring factions, its unrelenting thirst for cash – that a crisis is often close, though now further down the food chain than the England team and the Premier League. A televised meeting of 2025’s key actors is near unimaginable considering the secrecy many owners maintain, the global span from whence they come and many battles already being in camera through lawyers. The number of talking heads and influencers willing to step into the gaps is almost too grotesque to countenance. Snapshot to 1993 however, 14 months into the life of the Premier League, an entity barely mentioned over 40 minutes, and a room of football men are vehemently defending their corners. Just one woman is visible; the future sports minister Kate Hoey, and just one black face; that of Brendon Batson, deputy chief executive of the Professional Footballers’ Association. He remains wordless.

A raven-haired John Inverdale operates as a Robert Kilroy-Silk/Jerry Springer figure as various blokes in baggy suits – “some of the most influential and thoughtful people in football” is Inverdale’s billing – fight their corners. Here is a time before gym-buff execs, when male-pattern baldness is still legally allowed in boardrooms and exec boxes, when a moustache is anything but ironic.

“The whole game is directed towards winning rather than learning,” complains John Cartwright, recently resigned coach at the Lilleshall national academy, a less than gentle loosener. England’s Football Association is swiftly under attack from Hoey over being “out of touch”. Enter Jimmy Hill, a Zelig of football as player, manager, chair, the revolutionary behind the 1961 removal of the maximum wage, major figure – on and off screen – behind football’s growth as a television sport. Few have filled the role of English football man so completely and his responses to Hoey are dismissive, truculent. “You can only attack one question at a time and I find the attacks are so ignorant,” he rails, defending English coaching. Hill’s stance has not travelled well. Within three years, Arsène Wenger, among others, would be upending the sanctity of English coaching exceptionalism.

A short film from the ever gloomy Graham Kelly follows. The then-Football Association chief executive dolefully advertises his body’s youth development plan before David Pleat’s description of English youngsters as merely “reasonable” rather blows Kelly’s cover. Former Manchester City manager Malcolm Allison, by 1993 a long-lost 1960s revolutionary, declares England’s kids were behind Ajax’s as early as the late-1950s. “Big Mal”, demeanour far more On The Buses than On The Line, cuts the dash of ageing rebel, an Arthur Seaton still restless in his dotage, cast to the fringes as Cassandra.

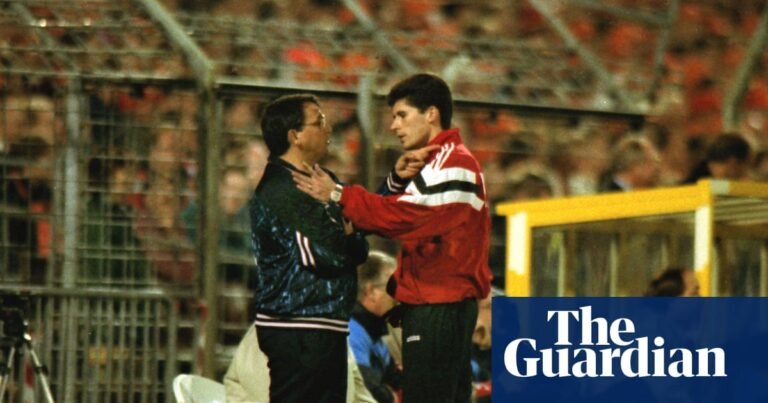

Jimmy Hill was a major figure behind football’s growth as a television sport

Next the programme’s wild card; Eamon Dunphy, footballer turned bestselling writer. The irascible face of Irish punditry for many decades seizes the stage with typical barbed lyricism, hunting down the stuffed shirts who run the game, full j’accuse mode adopted from his opening words. “English football has historically drawn its talent from the streets but unfortunately it has left its inspiration in the gutter,” he begins his own short film. Dunphy then lashes the “merchant class” that “have always wielded power”, kicks against the “subservient”, celebrating football’s “free spirited” outsiders.

“Football’s greatest men have usually been its saddest – ignored, betrayed or patronised,” says Dunphy, soon enough labelling English football media coverage as “banal”. “Where is football’s Neville Cardus?” he asks, referencing the Guardian’s legendary cricket writer, setting a slew of fellow journalists, including the late David Lacey, also of this parish, on defensive footings.

Cast in 1993 as rabble-rousing agent of chaos from across the water, Dunphy would declare himself an Anglophile in his 2013 autobiography, appreciative of the freedom found in 1960s Manchester compared to the illiberal Ireland he came from. Here he despairs for what made English football once so magical, bemoaning Allison’s estrangement and that Hill’s experience was also confined to the sidelines.

skip past newsletter promotion

The best of our sports journalism from the past seven days and a heads-up on the weekend’s action

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

Arsenal vice-chairman David Dein, a prime Premier League’s architect, is next for a Dunphy dagger. “You seem exceedingly smug about the idea of kids having to pay more for their identity” is a laser-guided attack on replica shirts being replaced each summer. It proves a tinderbox moment. Hill and Professional Footballers’ Association chair Gordon Taylor soon fly at each other. “Get yer facts right, Jim,” hisses Taylor as the subject of player wages ignites a bonfire fanned further by agent Eric Hall’s “monster monster” smirks.

Inverdale calls for order and concludes with a round-robin from which Pleat’s “you need an impossible man, a democratic dictator right at the top of football” sounds positively frightening. Somewhere in Pleat’s logic may lie the UK government’s imminent imposition of an independent football regulator, a process that led today’s power brokers into a sustained, bloody battle against such interference.

Fast-forward 32 years, through Premier League and Champions League dominance, international failures and successes, foreign talent and investment, profit and sustainability, splintering media landscapes, women’s football embodying national pride, much has changed and yet self-interest remains the darkest heart of English football.