It might seem shocking, at first, for an artist to use her own children as models in a work based on Medea, a mother from Greek myth who kills her sons. “They noticed the likeness in my work,” says Emma Talbot. “And I had to say, ‘Yes, it’s you.’” Talbot, whose first large-scale UK show has just opened at Compton Verney in Warwickshire, adds: “But when I think of ‘sons’, they’re the sons that come to mind. It was inevitable the images would be of them.”

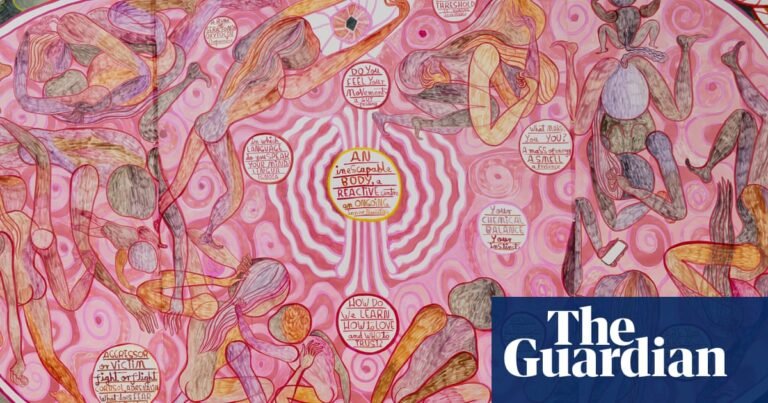

There’s another reason. The installation in which they appear – The Tragedies – is a tent-like, silk structure painted with intricate, swirling images interspersed with short texts: “Why should there be war?”; “Why fill the future with grief and regret?”; “What does war resolve?” These are the questions Talbot believes we should all be asking ourselves, at a time when the UK has been mooting the possibility of conscription. “It is a tragedy,” she says. “When they said that, I immediately thought of my sons, both in their mid 20s. It feels personal. These are my sons they’d be sending off to war.”

‘Personal’ … The Tragedies by Emma Talbot. Photograph: Courtesy the artist

This is the point Talbot wants to make with her Medea piece. “Her crime was totally unthinkable – and yet is what Medea did worse than us sending our children off to die in war? I can’t see that any kind of war resolves anything.” Talbot, a descendant of Jews who fled 1930s Germany, adds: “People say, ‘What would you have done in the time of Hitler, or over Ukraine?’ And I say, ‘If we had a system that didn’t legitimate aggression, everything would be different.’ We can’t even imagine how that world would be.”

I like the contrast between the lightness of the silk and the weight of the stories

War isn’t the only issue this show of fairly recent work tackles: Talbot uses paintings, sculpture and animation to examine other concerns, from our relationship with nature, to how grief affects our lives. Her paintings, all on silk, are colourful, closely packed with flowing imagery. They include a series called Magical Thinking, which explores the ways humans use imagination to make sense of the world. Sculptures include Gathering, which uses fabric, beads and wood to look at the symbolic properties of various animals. Her animation All That Is Buried shows a drawn figure navigating a soulless urban landscape in search of truth.

At the root of her work are questions about power. Who has it? What do they do with it? How might they use it differently? The Tragedies has long arms reaching out: they’re warning figures, says Talbot, like the chorus of a Greek tragedy. “They’re calling on us to notice what’s happening – because humans have the capacity to explore complex ideas. That gives me hope: there is scope to find another way.” All the same, she finds the news now unsettling. “I’m scared and my work reflects that.”

Talbot was born in the Midlands in 1969: her mum was a nurse, her father, seriously injured in a car accident, was her patient. The marriage didn’t last long: Talbot’s dad moved to Japan, where he still lives, to raise another family. Her mum remarried, but it didn’t make for a happy childhood. “She came from this intellectual German family and my stepfather worked in factories in the East End. It was complicated.” Talbot and her elder brother, three and five when their parents divorced, found their escape in drawing and acting. “The world was much more parent-centric then. Children had to carve out their own space.”

Complex ideas … A Journey You Take Alone by Emma Talbot. Photograph: Rolf K Wegst/Courtesy the artist and Kunsthall Stravanger

She did an arts course in Canterbury, then studied fine art at Birmingham Institute of Art and Design and did an MA in painting at the Royal College of Art. In the mid-1990s, while teaching art at Northumbria University, she met the sculptor Paul Mason, who she married. Their two sons, Zachary and Daniel, were seven and six when he died of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2006. It was an unthinkable turn – but for Talbot, it brought a new direction.

“Paul was the person I shared my stories with,” she says. “Then he wasn’t there any more. And that’s what life’s about, isn’t it? Sharing our stories. Suddenly there was this big void and I started to fill it with drawings – to get out the things I would have said to him.”

But still, she had overwhelming doubts. “I’d pay the babysitter and go to the studio and think, ‘I can’t do this any more. Maybe I’m not an artist after all.’ But slowly, I realised I had this incredible freedom again – just as I did when I was a kid.” Her art – previously paintings created using found photographs – changed. “I started to paint on silk. I like the contrast between the lightness of the silk and the weight of the stories. I like that silk is so light, so fluid.”

skip past newsletter promotion

Your weekly art world round-up, sketching out all the biggest stories, scandals and exhibitions

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

‘I could show myself honestly’ … Emma Talbot with one of her works. Photograph: Sara Sassi

Another work at Compton Verney is The Human Experience, two 11-metre long swathes of silk, wrapped around the gallery, taking the visitor on a journey through life, from conception to death. “It’s about how you move through a world that’s dangerous and uncertain. Because life experience comes from walking through volatility and uncertainty.”

In the midst of her grief, and while coping with life as a single parent, she realised she had nothing to lose, and everything to gain, by burrowing deeply into herself and making work that had little need of outside validation. “I realised I was finding a core version of myself. I could show myself honestly. I wasn’t concerned with what anyone would think. I thought, ‘This is about doing the work that matters.’ For me, art and life are indivisible.”

Following a residency in Italy, after she won the 2019 Max Mara prize, Talbot now divides her time between Reggio Emilia, in the country’s north, and the UK. Recognition on the continent has come easier than acknowledgment in Britain: she’s shown widely across Europe, with solo exhibitions ongoing in Copenhagen, Athens and Utrecht. Compton Verney ushers in a new chapter – but you get the sense it won’t change how she works. “Art is the glue between everything,” she says. “It’s there to help us make sense of the world. And making art is what I’ll carry on doing.”

Emma Talbot: How We Learn to Love is at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, until 5 October